Boogie Nights

“Boogie Nights (1997)”

Text By: Basil

Original Publication Date: August 4th, 2015

Boogie Nights is a cruel, condescending movie. A flurry of style that thinks it’s saying something broad and deep about the porn business as a metaphor for the 1970s, for the sense of Los Angeles hopefulness that was demolished by the cruel fist of the 1980s, for human beings in all their messy strangeness. But Boogie Nights hates its characters too much to be a meaningful study of their psychology. Thus its mean-spirited sense of humor can function only as satire. What, then, is it satirizing? The notion that people in the 1970s were too dumb and naive and hopeful to see their own downfall coming? Even ignoring the specious grasp of history this suggests, what good does that viewpoint do us? What do we gain from being asked to laugh at characters for not being smart enough to realize how doomed they are?

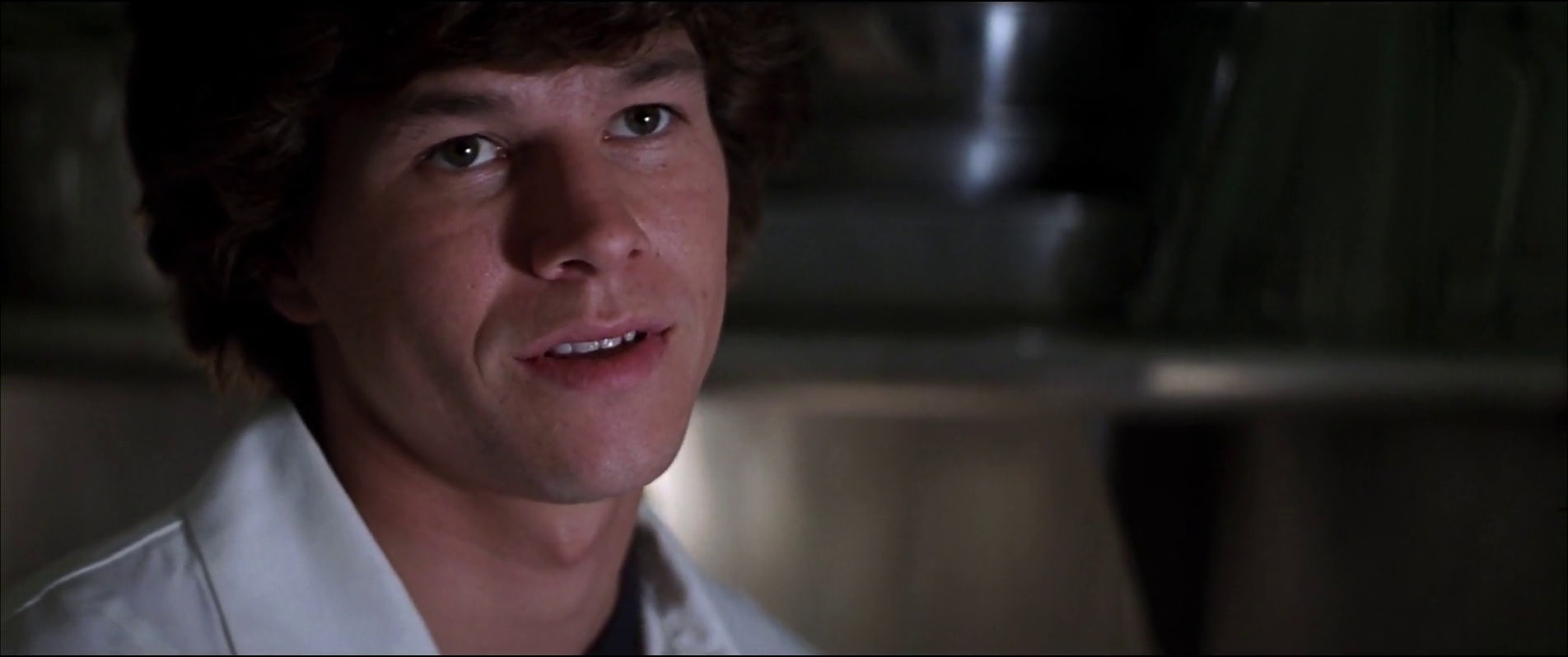

By now you all know the plot. Mark Wahlberg plays Eddie Adams, a dishwasher at a swinging night club in the San Fernando Valley who happens to have an enormous penis. Wahlberg, for me, is the standout of the film in its first half. Even as Paul Thomas Anderson encourages the audience to laugh at his naive enthusiasm and witlessness, Wahlberg works against this reading through a soft-spoken generosity that feels lived-in and nearly transcendent. He has a horrible home life and quickly adopts Burt Reynolds and Julianne Moore’s pornographer super-couple as his surrogate parents. Adams becomes Dirk Diggler, porno superstar and it’s nothing but glitz and parties and great times until 1980 hits and it all disappears. The plotting mirrors any number of rise and fall biopics, even if Dirk Diggler is more an amalgamation of a bunch of pornstar stories than any one person’s, and so the second half of the film takes on a darker tone with all of the half-baked dreams of these drug-addled optimists going straight into the toilet.

But, as I mentioned, to what end? In an early scene Reynolds’ porn director/mogul character, Jack Horner, explains his dream to Eddie/Dirk: he wants to create a movie so good that people will keep watching “even after they come.” Anderson plays this for laughs, of course. Porn plots, acting, dialogue, cinematography, etc. are terrible. The notion that they’re creating art makes Horner not just pretentious, but also stupid. Later, we cut from footage of John C. Reilly’s doltish sidekick declaring “Let’s go get some of that saturday night beaver” to Horner sitting in the editing bay declaring, “This is the best work we’ve ever done.” But the audience doesn’t see the sex, doesn’t see the part that might give his statement some level of credence. If pornography’s main purpose is to get people off, maybe it was the best getting off movie ever made. But comparing the film even to most low budget exploitation movies makes it impossible to take seriously. So what reaction do we have besides laughter at his idiotic sincerity?

But, as I mentioned, to what end? In an early scene Reynolds’ porn director/mogul character, Jack Horner, explains his dream to Eddie/Dirk: he wants to create a movie so good that people will keep watching “even after they come.” Anderson plays this for laughs, of course. Porn plots, acting, dialogue, cinematography, etc. are terrible. The notion that they’re creating art makes Horner not just pretentious, but also stupid. Later, we cut from footage of John C. Reilly’s doltish sidekick declaring “Let’s go get some of that saturday night beaver” to Horner sitting in the editing bay declaring, “This is the best work we’ve ever done.” But the audience doesn’t see the sex, doesn’t see the part that might give his statement some level of credence. If pornography’s main purpose is to get people off, maybe it was the best getting off movie ever made. But comparing the film even to most low budget exploitation movies makes it impossible to take seriously. So what reaction do we have besides laughter at his idiotic sincerity?

Versions of this scene appear throughout the film. Dirk taking Amber through his new apartment and poorly explaining what all his tacky decorations are (he won’t stop emphasizing that everything comes from Italy), Cheadle as Buck scaring off stereo customers with his intense love of country music, John C. Reilly trying to one-up Dirk at the party by bragging about how much he works out and doing terrible dives off the diving board, the fact that after they all see Dirk’s giant dick he literally wins the dick-measuring contest and becomes the alpha of the Reilly, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and Thomas Jane’s four-man group and the rest all start dressing like him and Hoffman buys the exact same car. It all gives the impression that we are supposed to laugh at these people. But there’s no deeper angle to the satire. People in porn are stupid? Some critics have called this a love letter to the late-1970s, or even to the 1970s porn world. I don’t see it. Other than a couple moments that are simply stolen from other, better, movies (Dirk leading a synchronized dance scene in a nightclub lifted from Saturday Night Fever), I never felt any true sense of fun from these early scenes, no legitimate celebration of this era. Everyone is so relentlessly naive and fresh-faced that the writing feels scrawled in blood all over the walls from the moment go. This cannot continue.

But the broad strokes of pathos that dominate this second half suffer from a tonal uncertainty that can’t decide if we should laugh or be moved. William H. Macy starts off the decline when his emasculated production designer finally can’t take his glib wife cheating on him anymore (this recurring gag is so childishly misogynist and tin-eared that I can’t believe I haven’t read anyone complain about it before) and kills his wife and her lover, the bullets timed perfectly with the New Year’s Eve countdown so that the muzzle blasts become fireworks, before sauntering into the room of stunned partygoers, giving a wan grin and then blowing his brains onto the back wall. Scorsese, the blatantly obvious influence everyone talks about when they talk about this movie, often uses violence in darkly comic ways but he also often sees his characters for the awful people they are. Much as sociopathic audience members might idolize them, Liotta, De Niro and Pesci are all pretty enormous scumbags in Goodfellas and Scorsese has almost no sympathy for their eventual fates. He is fascinated by their awfulness, sure, but that fascination is wrapped in self-loathing and ambivalent inquiry.

Anderson’s hatred feels accidental, as if he doesn’t realize he hasn’t given us enough to make the characters matter. What are we to make of the scenes where Amber represents herself in a custody hearing regarding her son, her ex-husband’s lawyer talking circles around her because she didn’t realize that loving her son wasn’t enough to get him back? Are we to laugh at the obviously ludicrous idea that she would be a good parent to her adolescent son? Are we to feel sympathy that she is so inside her life she can’t see that just because she wants him back doesn’t mean it’s a good idea for him? I can’t honestly believe that Anderson thinks we should feel the system is treating her unfairly, even though the looming face of Reagan behind the judge suggests his vitriolic policies to crack down on Welfare mothers and other “social improvement” projects that maligned many struggling working people. But nothing about Amber suggests she would be a healthy parent to any child. So when Anderson cuts to her sobbing into her hand outside the courthouse I am honestly not sure what emotion I am supposed to feel. Pity? Anderson mistakes condescending to a character for humanizing them.

With the exception of the Alfred Molina scene (which is very good and has been written about extensively) I feel this way about nearly every scene in the movie. I don’t like it. I don’t think what he has to say about psychological damage and surrogate families is particularly interesting or nuanced or even close to subtle. One of the best examples I can think of is the fight Eddie/Dirk has with his mother. She yells at him that he’s stupid and he cries and yells back that he is gonna be a big star and in the middle of the fight Anderson’s camera cuts to Eddie’s dad, sitting alone in his bedroom, emasculated and shamed that he can’t stick up for his only son. In a movie that wanted to explore this relationship, to give some kind of depth to this father-son-mother triangle, I could maybe accept that shot. In this movie, where the mother exists only to hate her son and push the plot forward, I find it disgusting. In co-opting the relationship dynamic of Rebel Without a Cause but stripping it of both its 1950s context and its centrality to the film’s overall plot, Anderson creates an ugly misogynistic shorthand that feels like something out of a sitcom, except taken completely seriously. Why not have both parents be assholes? Why the domineering mother and weak, helpless father? To make Jack Horner that much more appealing in his warm, ebullient decisiveness? It’s lazy psychology. A + B always equals C. J.J. Abrams takes a lot of (deserved) guff for relying on father-child conflict to drive a lot of his characters’ psychologies. Where’s that same exasperation for Anderson, who is nearly as transparent and phony about it?

-Basil, 2015